An excerpt from the 2024 Family Medicine Update Oct. 23 – 25.

The crisis of synthetic opioids is driving a surge in overdose deaths across the United States and globally, creating a public health emergency. Synthetic opioids such as fentanyl, and even more recent drugs such as benzimidazoles, are contributing to a deadly “third wave” of the opioid epidemic. Dr. Fantegrossi spoke on the growing issue of “poly-drug use”—the simultaneous use of multiple drugs.

How Opioids Work and Why Synthetic Versions Are So Potent

Opioids are a category of drugs that relieve pain by binding to specific receptors in the brain, called opioid receptors. When these drugs attach to these receptors, they block pain signals and release a surge of dopamine, which produces feelings of pleasure and relaxation. However, opioids also suppress respiration, which makes them highly risky in overdose cases.

Opioids come in several forms:

- Natural opiates: These include drugs like morphine and codeine, derived directly from the opium poppy plant. They are used medically to treat pain but are generally less potent than synthetic versions.

- Semi-synthetic opioids: Examples include oxycodone and hydrocodone, partially derived from opium but chemically modified in labs.

- Fully synthetic opioids: These are entirely lab-created with no natural components. They include fentanyl, methadone, and newly emerging drugs such as protonitazines and benzimidazoles.

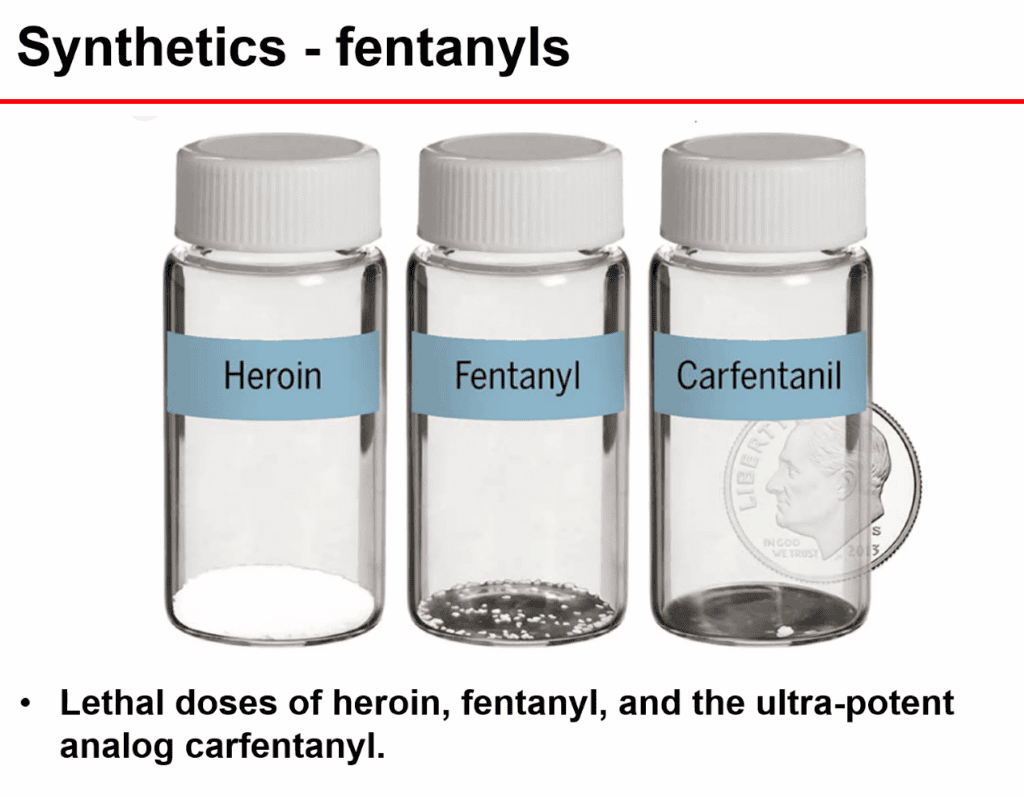

Synthetic opioids interact with the same brain receptors as natural opiates, but they are far more potent. For example, fentanyl is estimated to be up to 100 times stronger than morphine and requires only a minuscule dose to create a significant effect. This extreme potency is a double-edged sword: while synthetic opioids can provide rapid pain relief, even a slight overdose can result in a fatal respiratory shutdown.

The Third Wave of the Opioid Crisis: Synthetic Opioids

The opioid crisis has seen three waves. The first was driven by prescription opioids such as oxycodone. The second saw the rise of heroin as people transitioned from prescription pills. The third is synthetic opioids, primarily fentanyl. Fentanyl and similar drugs are especially dangerous because they are cheap, widely available and have an almost immediate impact on the brain.

Dr. Fantegrossi said that even a few milligrams can be fatal. This is particularly risky because synthetic opioids are often mixed with other drugs, such as heroin, cocaine or even counterfeit prescription pills, to enhance their effects.

Emerging Synthetic Opioids: Benzimidazoles, Protonitazines and the Challenge of Detection

Although fentanyl is the most well-known synthetic opioid, new opioids are ever emerging. Among the most concerning are the benzimidazoles and protonitazines, found increasingly in street drugs. Benzimidazoles, for example, were initially developed as tranquilizers for animals. They are powerful drugs and are significantly stronger than traditional opioids, meaning even a tiny dose can be deadly.

One of the bigger challenges with these newer synthetic opioids is their molecular structure, which often differs greatly from traditional opioids such as heroin or morphine. This means they may not show up on standard drug tests, which complicates detection for providers, law enforcement and toxicologists.

New synthetic opioids also grip more tightly to the opioid receptors in the brain. With such a strong bond, reversing an overdose is difficult with standard treatments such as naloxone (Narcan). Dr. Fantegrossi noted that naloxone works by displacing opioids from brain receptors. However, naloxone struggles to unbind new synthetic opioids from receptors, meaning it can only partially reverse an overdose or may fail.

The Growing Threat of Poly-Drug Use

Poly-drug use (multiple drugs consumed together) is increasingly common. Some people intentionally combine substances to intensify or prolong the effects of their high. However, many people are unaware that they are consuming multiple substances. For example, fentanyl is often found in drugs like cocaine, methamphetamine and counterfeit pills, meaning that a person using a drug recreationally could be exposed to fentanyl without knowing it. This accidental exposure is one reason overdose deaths have surged in recent years.

The effects of poly-drug use are highly unpredictable and dangerous. When stimulants such as cocaine or methamphetamine are mixed with opioids, they create a “speedball” effect, where one drug stimulates the body and the other depresses it. This puts heightened stress on the heart and respiratory system.

A particularly deadly combination is fentanyl mixed with Xylazine, a powerful veterinary sedative not approved for humans. Xylazine is used to sedate large animals such as horses and cattle, so when added with fentanyl, Xylazine greatly increases the risk of respiratory depression which leads to an even higher chance of fatal overdose. Users often report large, painful skin wounds and infections that are tough to treat. These wounds can appear even in parts of the body where no drugs were injected, which adds to the mystery and danger of Xylazine.

Why Naloxone May Be Losing Its Effectiveness

Naloxone has been the go-to treatment for opioid overdoses, but it’s limited when it comes to treating overdoses involving newer synthetic opioids.

One issue is that naloxone’s effects are short-lived. It can temporarily block opioids from brain receptors, but it does not stay in the body for long. Synthetic opioids such as fentanyl and benzimidazoles often have longer-lasting effects. This means that even if naloxone initially reverses an overdose, the person may slip back once the naloxone wears off, a condition called “rebound overdose.”

Dr. Fantegrossi suggested that naltrexone might be a useful alternative or addition to naloxone. Unlike naloxone, naltrexone lasts longer in the body. It’s not widely used in emergency settings because it’s more expensive and has a slower onset than naloxone. Dr. Fantegrossi proposed a combination approach: naloxone administered first for quick reversal, followed by naltrexone for lasting effects.

Legal Loopholes and Synthetic Cannabinoids

As governments crack down on synthetic opioids, drug manufacturers respond by crafting new, unregulated drugs that bypass existing laws. For example, as authorities have regulated fentanyl, drug makers have developed synthetic cannabinoids and new classes of opioids like benzimidazoles that are not regulated. This ability to evade legal restrictions makes the synthetic drug crisis difficult to manage and keeps healthcare providers in a constant struggle to keep up with new threats.

One significant risk is synthetic cannabinoids, sometimes called “fake weed,” “K2” or “Spice.” These drugs are engineered to mimic the effects of THC, the active compound in marijuana. But synthetic cannabinoids are far more potent, often leading to severe side effects including seizures, psychosis and even death. Synthetic cannabinoids are often sprayed onto dried plant material, making them resemble marijuana. They are available at gas stations, convenience stores and online, which makes them easily accessible, especially to young people.

Synthetic cannabinoids are now found in opioid products on the street, and fentanyl is increasingly found in synthetic cannabinoids. This accidental exposure can be deadly in that synthetic cannabinoid users may not know they’re exposed to opioids. Naloxone also might not work in these cases since it is designed to reverse opioid overdoses, not those caused by cannabinoids. Dr. Fantegrossi noted that synthetic cannabinoids can also suppress respiration, similar to opioids, adding another layer of danger to poly-drug overdoses.