Edith Irby Jones and the Integration of Medical Education in the South

September 2018

By Erick Messias, M.D., Ph.D., M.P.H.

Associate Dean for Faculty

Professor, Department of Psychiatry

College of Medicine

University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences

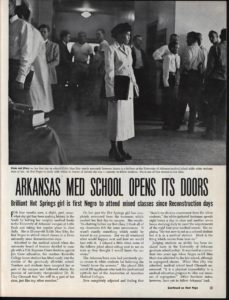

Seventy years ago this September, the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences College of Medicine made history. In those final summer days of 1948, Edith Irby Jones started her medical studies and thus became the first African-American to enroll in an all-white medical school in the South. It had taken the college, founded in 1869, 69 years to do so, in a state with a significant proportion of African Americans. As we celebrate this anniversary, this short essay will address the three simple questions: why her, why 1948, and why Arkansas, so that we can realize why it still matters today.

Why Edith?

At the center of this story is a remarkable human being. Edith Irby was born December 23, 1927, in Conway. Her mother, Mattie Irby, worked as a domestic and picked cotton. At age 3 her father, a sharecropper, died after being kicked by a horse. An older sister, Juanita, died of typhoid fever. Following these losses Mattie moved with her daughter to Hot Springs in search of better educational opportunities. The move paid off, as Edith excelled academically, graduating with honors in 1944. She moved to Tennessee to attend Knoxville College, a historically black college, where she maintained an A average while participating in Delta Sigma Theta sorority, the debating team and drama club, and working as a typist and office assistant. She graduated cum laude, earning a Bachelor of Science with a major in chemistry and minors in biology and physics. With this background, she took the Medical College Aptitude Test (MCAT) and applied to eight medical schools in early 1948.

Why 1948?

For most of the first half of the 20thcentury the vast majority of African Americans wanting to become physicians were admitted to two historically black medical schools: Howard University in Washington, D.C., and Meharry Medical College in Nashville, Tennessee, with a few admitted through restrictive quotas in schools outside the South. In 1935, under the leadership of Charles Hamilton Houston, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) began a campaign to dismantle legalized segregation. Until then, the opportunities for education were cemented in the 1896 Supreme Court decision Plessy v. Ferguson, which established the principle of “separate but equal.”

The situation for professional and graduate education, however, was later described by legal scholar Mark Tushnet as “separate but nonexistent.” Given the constitutional precedent, the strategy adopted by Houston, along with future Supreme Court Justice Thurgood Marshall, was to mount a challenge based on the inequality of opportunities for African Americans. They sought qualified students to apply to graduate schools, aiming to sue if they were not accepted. Their break came with the application of Lloyd Gaines in 1935 to the University of Missouri Law School. They sued in county and state courts and lost, leading them to the Supreme Court. In a 6-to-2 majority, the Supreme Court decided in 1938 that out-of-state scholarship programs and the absence of a separate law school denied African Americans equal protection.

The Gaines decision was heard throughout the South. States with graduate schools receiving public funds now had only two options: to accept a qualified applicant or create a separate but equal school for African Americans. This second option led to the creation, in two weeks, of a law school in Oklahoma for a single student. That student argued that his education would not be equal and refused to enroll, and the courts ordered his admission to the University of Oklahoma Law School. The student, Ada Lois Sipuel, would finally gain admission in 1949.

Why Arkansas?

Officials in Arkansas were paying attention to these decisions occurring in neighboring Missouri and Oklahoma. The state passed a law offering out-of-state tuition grants for African-American students seeking graduate degrees in fields not available in Arkansas. This program supported a few students studying medicine at Meharry – though it was in violation of the Supreme Court ruling in Gaines. The costs associated with building and maintaining separate graduate schools for African Americans was believed to be prohibitive given Arkansas’ financial situation. With the constitutional precedents in mind, University of Arkansas President Lewis Webster Jones announced in January 1948 a new policy stating that qualified African Americans applying for graduate programs would be accepted.

With “accommodations,” Silas Hunt, a World War II veteran and honor graduate of the Arkansas Agricultural, Mechanical and Normal College (AM&N) in Pine Bluff, was admitted to the Law School in Fayetteville in February 1948. These accommodations included separated classrooms and no access to bathrooms or to the library; books were brought to him. Hunt thus became the first African American admitted to a graduate school in the South. Tragically, he died of tuberculosis in April 1949.

In the meantime, Edith Irby’s application to UAMS was ranked 28th among 230 applicants, prompting Dr. H. Clay Chenault, Dean of the College of Medicine, to summon the university’s president since, as he put it, “we have a problem.” President Lewis Jones concluded their conversation with a landmark decision to “proceed according to the policy, and admit her.” In order to prevent the accusation that Edith Irby would be taking the place of a white student, the board of trustees increased the class size from 90 to 91 that year. A headline in the Arkansas Democrat on September 28, 1948, stated “91 Freshmen Enter UA Medic School.”

Dean Chenault decided against segregated academic accommodations, stating that “it’s physically impossible to offer any measure of segregation in a program of medical education.” However, bathrooms and dining facilities continued to be segregated. The university decision was made in the spirit of academic autonomy and thus Arkansas Governor Ben Laney was not informed. When Laney learned of the developments at UAMS, he proceeded to blast the decision, exclaiming, “the point is they pushed white boys aside for this Negro.”

There were other heated expressions of disapproval of Edith Irby’s admission to the college. Letters to the Dean included opinions such as “this is a crime against nature” or that “a negro girl attending medical school made our Southern blood boil” and the contention that Arkansas would be “disgraced.”

There were supportive letters as well, including one from African American classical composer and Little Rock native Florence B. Price, who expressed her joy and pride over the decision and in particular about the Dean’s declaration that “she will be part of her class, just like other members” – saying it was all she wanted from her home state. Irby’s admission made national news in Time and Ebony magazines, the latter publishing a five-page article on her.

Irby’s medical school days had several heartwarming moments. In the segregated area where she ate, she would find fresh flowers left by unnamed kitchen staff, and at times her classmates flouted state law and joined her. Black citizens from Hot Springs donated money to pay her tuition, and during her four years in school she continued to receive envelopes filled with cash along with “words of encouragement and blessings.”

In 1950 Irby married Dr. James B. Jones, a psychology professor at Arkansas AM&N. Meanwhile, key support came from her classmates, in particular the large group of World War II veterans who “formed a protective shield” around her. She also became close with her class’s two other female students, who would have to stand together when traveling by bus due to segregated seating. But together they stood. On June 16, 1952, she received her medical degree, becoming Dr. Edith Irby Jones.

Dr. Jones’ medical career started in Hot Springs, where she practiced for six years until moving to Houston, where she became the first African American woman admitted to the internal medicine residency at a Baylor Affiliated Hospital. In 1985, she became the first woman president of the National Medical Association. She has been honored by the American Society for Internal Medicine and the American College of Physicians.

Importantly, Dr. Jones was a seed that flourished in the UAMS College of Medicine in the forms of hundreds of students, residents and faculty members, including one Surgeon General of the United States (Joycelyn Elders, M.D., a 1960 graduate and longtime faculty member), several department chairs, and one Dean (E. Albert Reece, M.D., Ph.D., M.B.A., who led the college in 2002-2006).

Each of us owes those individuals, in turn, for the good they have done over these many years, treating patients, teaching students, contributing to discoveries in research, and providing role models for new generations of young African Americans so that they can see themselves as physicians, caring for others and in the process healing our nation.

Why it Still Matters

It is with this background that one can understand today the momentous decision of the College of Medicine to accept Edith Irby in 1948. Although she has described the process as “no struggle, no fight, no court battle,” it was in fact the product of a long struggle that included both fights and court battles. The seamless way it occurred at UAMS earned praise from the NAACP at the time when its assistant secretary declared that “Arkansas whose record is less liberal, tolerant, and progressive than states such as Kentucky, Virginia, North Carolina, and Missouri had been the first to open its graduate and professional schools to African Americans.”

This story reminds us of the long-view judgment of history. If we look at our nation today, who would stand with Governor Laney’s segregationist views and who would stand with the Dean of the College who decided no “accommodations” for segregating classes would be necessary? Who today would build barriers, or walls, and who, if it were still the law, would sit in that segregated area to share a meal?

And how will people in 2088, 70 years from now, see our decisions and, most importantly, our actions when it comes to how we treat minorities and other groups of disenfranchised persons?

The story of Edith Irby Jones reminds us where we’ve been, how much we’ve overcome, and how long we still have to go to ensure fairness and justice for all of us.

Editor’s note: Dr. Edith Irby Jones passed away on July 15, 2019.

Acknowledgements

- UAMS Center for Diversity Affairs

- UAMS Library and Historical Research Center

- UAMS Faculty Center

- Vanessa Gamble, M.D., George Washington University

- Tom South, Assistant Dean for Admissions, UAMS College of Medicine

- David Ware, Ph.D., Arkansas Capitol Historian