The Women’s Faculty Development Caucus (WFDC) was established in 1989. Its mission is to inspire, encourage, and enable women physicians and scientists to realize their professional and personal goals. The WFDC seeks to increase the number of women in leadership positions. In 1997, the WFDC won the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) Women in Leadership Development Award that recognized the Caucus as being on the leading edge of professional development for women faculty in academic medicine.

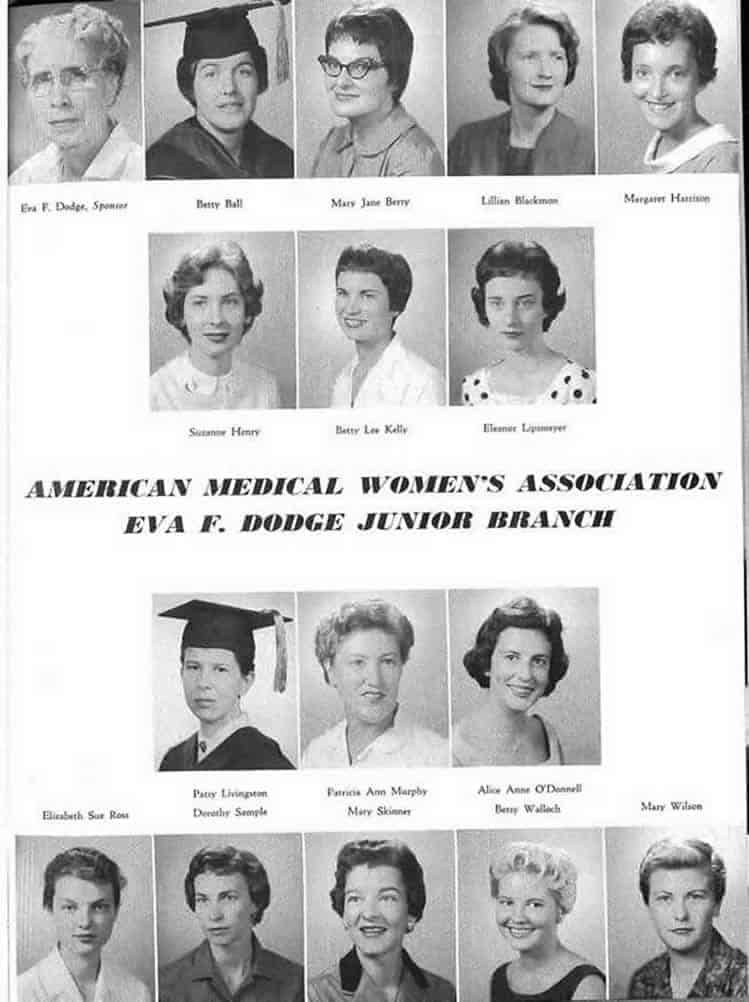

Our Heritage

Women who wanted to become physicians had few options when medical schools were in their infancies. They had to find a men’s medical school that would allow an exception or attend a medical school established for women only. While women didn’t begin enrolling in medical schools nationwide until the mid-19th century, most schools were very resistant to permitting females and the shift in academic medicine did not occur until decades later.

Perhaps the story of women in medicine at the COM begins with Annie Schoppach, the first female graduate of the Medical Department of the University of Arkansas. In fact, she is the first woman listed in any capacity at all at UAMS. She entered medical school in 1897 and graduated with her class of 20 in 1901. Initially, she opened her office on Main St. in Little Rock before buying the house on State Street that served as her office and maternity hospital for the rest of her life. In the decade after Schoppach graduated from medical school, four other women joined her in the profession.

Ida Josephine Brooks was among Arkansas’ earliest women physicians and the first female faculty member at the University of Arkansas Medical Department. Spending 15 years as a teacher in Arkansas, she was refused admission to the Department in 1887 because of her gender. She graduated from the Boston University School of Medicine, one of the earliest medical schools to accept women, and returned to Little Rock to establish a private practice and become an associate professor of psychiatry.

Increasing numbers of women were admitted to medical schools during the mid-1800s. Financial forces aided their entry as supporters of feminism made major contributions to schools accepting women. By the late 1800s, several previously all-male schools were admitting and graduating women, and legislators allowed the charters of medical schools specifically for women. Social acceptance also grew as women physicians increased their visibility by giving lectures on topics such as hygiene.

Eventually more women began to populate the medical school as both students and faculty members. Mollie King became the first full-time female faculty member at the school in 1917. A professor of pathology, she also paved the way for research activity at the school. She was an active researcher who worked with the head of the Department of Pathology and Bacteriology to investigate problems like the toxicity of cigarette, cigar, and pipe smoking, the actions of drugs on the vagus center of the medulla, and the bifurcation of the seventh cranial nerve long before others considered research in these fields.

The trend toward female medical students continued throughout the early 1900s, correlating with a national movement for female suffrage and women’s rights. Many times, these future physicians faced barriers when it came to obtaining clinical experience in the classroom and laboratory.

Another feat for women in medicine, Edith Irby Jones became a national role model when she became the first African-American student enrolled at what had been a segregated medical school. This accomplishment was reported nationally in many publications, including Life, Time, Ebony, and the Washington Post. Famed Little Rock civil rights activist Daisy Bates provided the funds for Jones to attend the School of Medicine. Due to state laws of the time, Jones had to use a separate bathroom and she ate her meals alone in a separate room from the other students. She earned her degree in 1952. Get more information about Dr. Jones.

These are just a few examples of the countless women who impacted the history of the College of Medicine and brought distinction and honor. A lot has changed since the first pioneers led the efforts for the women’s medical movement. It was not until the 1990s that the numbers of female and male medical students matriculating truly began to reach parity. Today, women compose more than 50 percent of the College of Medicine’s freshman medical school class.

Nationally, women now comprise nearly half of incoming medical students and represent over a third of all practicing physicians. Alternately aided and hindered by education and by opportunities to practice, women have persisted throughout time and shifting social, religious, and scientific ideologies to make strides in medicine.