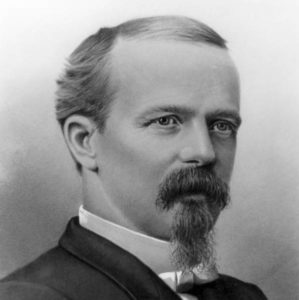

By Fred O. Henker, M.D.

Early in Arkansas statehood, there was a great need for adequately trained physicians and a facility for training them. Dr. Southall was qualified to meet both needs.

Dr. Southall was one of the most respected gentlemen in Little Rock during his time. He came from a distinguished Virginia family, which included early settlers enthusiastically patriotic in the formation of our country and leaders in the Revolutionary War and War of 1812. A great uncle, James Barrett Southall, was once owner of Raleigh Tavern in Williamsburg. Both his father, Turner Harrison Southall, and his grandfather James Barrett Southall, were revered Virginia physicians. The fifth of seven children of Dr. Turner Southall by his second wife, Alice Wright, James was born Nov. 5, 1841 in Smithfield, Va., and spent most of his boyhood in Norfolk. He received his early education there and in North Carolina.

He began his medical studies under Dr. Robert Turnstall of Norfolk, leaving at 17 to attend medical lectures at University of Pennsylvania in 1859. With war clouds looming he transferred to University of Louisiana (Tulane) where he graduated March 1, 1861 at the age of 19. For reasons unknown, his address at this time was given as Little Rock, Ark.

Soon after graduation, Dr. Southall volunteered in the Confederate Army, and was assigned to the 55th Regiment, Virginia Infantry, Army of Northern Virginia at the rank of assistant surgeon, then promoted to full surgeon June 25, 1862. On July 5, 1863, he was wounded at Gettysburg and taken prisoner until paroled and exchanged at Fort McHenry on Dec. 3, 1863. On April 9, 1865 his unit was surrendered by General Robert E. Lee at Appomattox shortly after which he was paroled and discharged.

Dr. Southall returned to Norfolk and entered general practice but after nine months moved to Memphis, Tenn. There, he met and eventually was married in 1869 to Olivia Gertrude, daughter of Major John James Murphy and granddaughter of Reverend William Mitchell, D.D. pioneer Episcopal missionary serving between 1839-1843 at Pine bluff, Hempstead County, Fort Smith, Van Buren and Choctaw Nation. The marriage was blessed by two daughters, Alice Gertrude and Edith May. Leaving Memphis, he practiced five years at Marion, Crittenden County, Arkansas, then came to Little Rock in 1872. Establishing his office at 125 Main Street, above Hughes Drug Store, he soon was considered one of the community’s most respected and public-spirited physicians. He was known as a systematic scholar with a memory for details. Also, he became active in city, county and state medical organizations as well as the American Medical Association and the Medico-Legal Society of New York.

Unfortunately, Dr. Southall arrived just in time to become embroiled in the infamous Almon Brooks dispute, which split both the county and state medical organizations. Taking a conservative stance, he expressed his sentiments: “My acquaintance with the inside manipulation of medical organizations, particularly this state, within the past five years affords me the ample proof that under the regime your society proposes, the same cannot result in either professional scientific attainment nor society intimacy or fraternity among the profession of the state. To join the seceding physicians for no purpose other than harmony would be a humiliating course.”

Evidently differences were resolved as Southall joined Dr. P. O. Hooper in the formation of the Medical Department of Arkansas Industrial University in 1879, being appointed professor of physiology until 1886 when on the resignation of Dr. Hooper he assumed professorship of Theory and Practice of Medicine. It appears that association with the medical school added greatly to his recognition and prestige as his private practice in 1879 grossed $3,200 and increased to $4,600 by 1883. He became president of the Arkansas medical Society in 1882. It was said that he did more for medical legislation than any other member of the state society.

The Southall family lived comfortably in Little Rock. In 1888, they built a magnificent brick home at 804 West Third, with Thomas Harding superintending the construction. The doctor’s accounts reveal signs of their lifestyle: Occasional ice cream at $1.00, keeping a bird as evidenced by 50 cent purchases of bird seed, cigars, or tobacco, at $.50, whiskey at $4.00, oysters $.50 and from 1881 a telephone at $3.50 per month. The church received occasional offerings of $1.00 and $2.00 but the name and denomination are not mentioned. Other necessities covered a buggy for $285, oats and bran $4.50, cleaning the well $3.00 and in December 1880, a cradle for $4.00, toys for $5.00, wood $10.00, coal oil $.25, and coal $6.00. There were weekly payments of $2.25 to Leroy, evidently a servant. Through the accounts were also $1.00 to $5.00 payments to “Gertie.”

Around 1887, a lesion appeared in Southall’s mouth, which proved to be malignant, leading to a long terminal illness. He spent several weeks in New York seeking a cure to no avail. Closing his practice in 1900 he died July 22, 1901. After a funeral at the family home, he was entombed in the family mausoleum in Oakland Cemetery attended by the entire medical society en masse. Active pallbearers were Drs. L. R. Stark, R. H. Chester, F. Vinsonhaler, J. H. Lenow, E. R. Dibrell, G. M. O. Cantrell, L. P. Gibson, and J. A. Dibrell. His life was an inspiration to his profession, a comfort to his patients and an asset to his community.