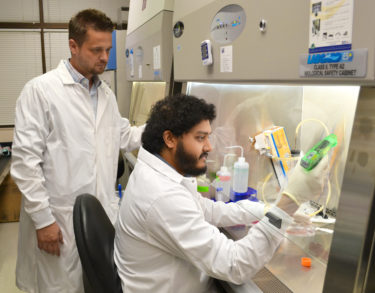

Roger D. Pechous, Ph.D., studies the bacteria that caused the infamous black death of the Middle Ages, shedding light on something old to potentially protect against something new: bioterrorism. The University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences (UAMS) researcher’s latest work has been published in Infection and Immunity.

Pechous is an assistant professor in the Department of Microbiology and Immunology in the UAMS College of Medicine. The article, titled “Modeling Pneumonic Plague in Human Precision-cut Lung Slices Highlights a Role for the Plasminogen Activating Protease in Facilitating Type 3 Secretion,” has been published online in advance of the August print edition of the journal.

The bacterium is called Yersinia pestis. Pechous and Srijon Banerjee, a postdoctoral fellow in Pechous’ lab, study pneumonic plague, the severe lung infection caused by Yersinia pestis as it spreads from human to human through inhalation. The World Health Organization (WHO) classifies pneumonic plague among the world’s deadliest infectious diseases. When the bacterium is spread by fleas, it is known as bubonic plague. Plague in the bloodstream is called septicemic plague.

“Y. pestis was responsible for three major pandemics in recorded history and continues to be a potential threat worldwide, primarily due to concerns of its release as a weapon of bioterror,” Pechous said. “Human-to-human transmission of plague occurs via the lungs, and is almost always lethal in the absence of timely treatment.”

Banerjee said death from pneumonic plague typical occurs in four to seven days. If antibiotics are not administered within 24 hours of symptom development, it is nearly 100% fatal. It is one of the deadliest bacteria known to man.

“What was unique about this study was its use of real human donor lung tissue, prepared to maintain realistic lung function in the laboratory setting,” Banerjee said. “This allowed us to observe the way Y. pestis would behave in a living human lung and see what makes it so successful at overwhelming its human host.”

Human lung tissue is cut into slices for the experiments in the Lung Cell Biology Laboratory at the Arkansas Children’s Research Institute by coauthor Richard C. Kurten, Ph.D., a professor of physiology & biophysics and pediatrics at UAMS. Kurten routinely acquires lungs from organ transplant donors and processes them for use in research in his laboratory and those of collaborators at UAMS and across the country.

From watching the behavior of Y. pestis in the lung slices in the lab, the researchers were able to pinpoint exactly how the bacteria quickly gains the upper hand.

“We show that Y. pestis hones in on a key cell type and delivers key proteins that interfere with its ability to control infection and initiate an immune response,” Pechous said. “We identify a protein on the surface of Y. pestis that is critical for directing Y. pestis to specifically target this cell type to establish infection.”

“All of this happens quickly,” Banerjee said. “By the time other signals alert the immune system to the severity of the infection, it’s too late. Ultimately, your own immune response is what ends up compromising lung function and leading to death.”

Understanding this process has applications for pneumonic plague and beyond.

For one, it’s important to better understand how Y. pestis functions, so scientists can develop better treatments for the highly contagious infectious disease. While rare today in humans, plague continues to be carried in animals and fleas, from which it can spread to humans.

For example, a 2016 outbreak in Madagascar infected 62 people, killing 26, according to the WHO. Another Madagascar outbreak in 2017 infected 2,348 people, causing 202 deaths. In the United States, the Centers for Disease Control reports an average of 1-17 cases per year, mostly in the West, where the disease is carried by rodents.

In addition, the progression of Y. pestis infection in the lungs mimics other lung infections, like severe pneumonia, but on a much faster scale. More broadly, understanding the bacterium helps scientists and public health officials plan for containing disease outbreaks. The research could also lead to the development of alternative treatments, which could be useful if the bacterium ever becomes resistant to antibiotics.

Pechous earned his doctorate from the Medical College of Wisconsin and completed postdoctoral training at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. He has been studying bacterial infection since 2001. Banerjee earned his Ph.D. from the University of Calcutta in India.

The Pechous lab is another successful example from the UAMS Center for Microbial Pathogenesis and Host Inflammatory Responses, directed by Mark Smeltzer, Ph.D. The center has earned $21 million in funding through the NIH’s Centers of Biomedical Research Excellence (COBRE) program, which aims to provide funding and mentoring to researchers who are early in their careers. Its participants are studying viruses, malaria, cancer, Lyme disease and chlamydial infection. Pechous’ work is funded by the center and a grant from the NIH National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases.

UAMS has six COBRE centers, which are launching new scientific careers, attracting top talent and creating concentrations of expertise on topics like neuroscience, cancer therapy, childhood obesity prevention and pediatrics.

In order to study Y. pestis at UAMS, the Pechous lab uses strict containment facilities and security procedures.

Infection and Immunity is a prestigious peer-reviewed journal published by the American Society for Microbiology that reports key discoveries that help microbiologists, immunologists, epidemiologists, pathologists and clinicians gain new insights into the underlying mechanisms of host-pathogen interactions and develop novel strategies to prevent or treat infectious diseases.