Malrotation

Ah, “malro”, the colloquial term you already are or will be all too familiar with on your children’s rotations!

What is it?

Abnormal twisting of the bowel during fetal development leading to problems with feeding in the neonatal period. Not all malrotation is volvulus, in fact a lot of children survive to adulthood with congenitally malrotated bowels just fine and have these malrotations incidentally discovered (see second CT cine stack). But yes, malrotation of the bowel can certainly predispose to volvulus; obstruction and bowel necrosis which is why we worry about it in the setting of bilious vomiting.

How does it happen?

Bowel starts to develop around the five-week mark during normal embryonic development, however the rate of growth of the bowel exceeds that of the abdominal cavity, and the bowel is extruded into the omphalomesenteric sac before being brought back into the peritoneal cavity at the 10th week of gestation. During this process, the bowel undergoes a 270-degree counterclockwise rotation around the superior mesenteric pedicle/SMA to assume its final resting position in the abdomen with the ligament of Treitz in the left upper quadrant and the cecum in the right lower quadrant, followed by fixation of the broad mesentery extending from the duodenojejunal flexure in the upper left abdomen to the cecum in the lower right abdomen at the 12th gestational week (13, 14, 15). When the normal process of intestinal rotation and attachment fails, non rotation or malrotation results (occurring in an estimated 1/500 live births) (2). The failed intestinal rotation presents as an abnormally positioned bowel with a right sided/low midline (instead of left) duodenal jejunal flexure and/or a high medially located cecum as well as a shortened mesentery. Malrotation in and of itself is asymptomatic, making the true incidence hard to determine as patients may live their entire lives without knowing they are malrotated. Malrotation predisposes patients to midgut volvulus, thus making the findings very important to know, as any patient with known malrotation will have a laparoscopic Ladd’s procedure done (20). In malrotation the mesenteric band which tethers the small bowel is markedly shortened resulting in an increased potential for twisting around the superior mesenteric artery. This twisting is termed midgut volvulus and is a surgical emergency commonly presenting in infancy with bilious emesis.

What do I need to know?

Well, first know when to raise suspicion for it. Findings are non specific on X-rays. Even if you see distal bowel gas or normal bowel gas pattern in a kid who’s coming in with bilious emesis, do think about malrotation.

Ultrasound can be helpful in demonstrating the relationship of the retroperitoneal duodenum and the superior mesenteric vessels. Color Doppler can show the superior mesenteric vein swirling with the small bowel loops around the superior mesenteric artery. This is also known as the “whirlpool” sign and is seen in midgut volvulus (16, 19). Another sign to know is the SMA cutoff sign, in which the SMA abruptly ends (in the middle of the whirlpool). This denotes the precise area of twisting and vascular impingement which makes this diagnosis such an emergency. While upper GI is still the gold standard for diagnosis of midgut volvulus, ultrasound is quickly showing that it is a better initial option.

Note the beautifully represented whirlpool sign on this cine color doppler exam of the bowel compatible with malrotation complicated by midgut volvulus. The whirl you see here is made by the swirling appearance of the mesentery and superior mesenteric vein around the superior mesenteric artery. The direction of the swirl is clockwise on ultrasound. Simply put, this sonographic sign is the corollary of the corkscrew sign seen on UGI studies.

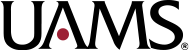

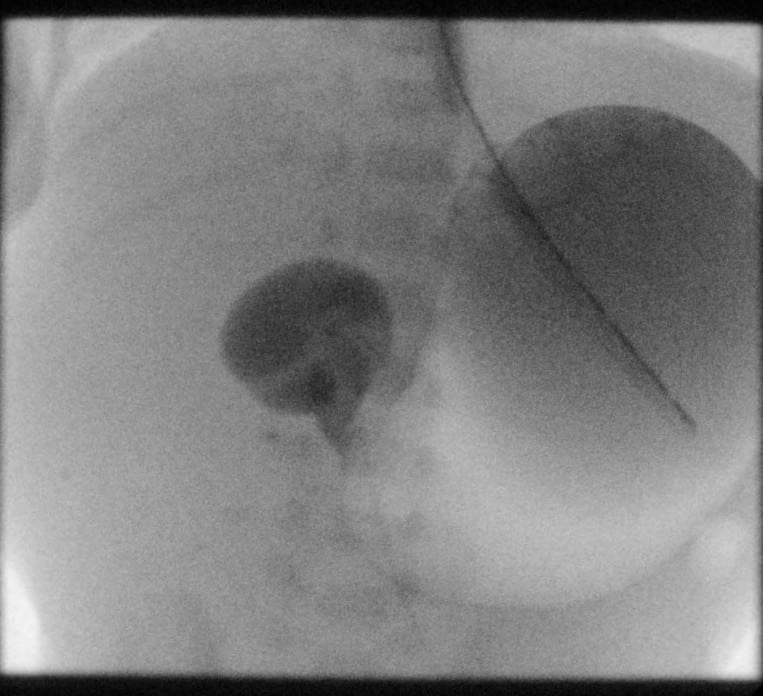

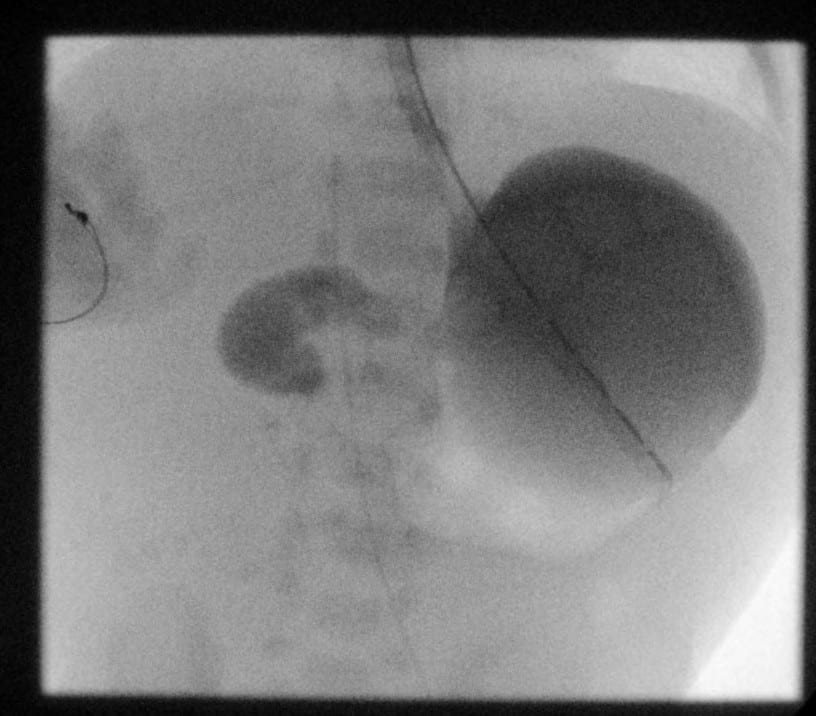

Characteristic findings on upper GI study include a dilated, fluid filled duodenum, proximal small bowel obstruction and “corkscrew” duodenum/proximal duodenum with a spiraling outline (1, 16). The duodenojejunal junction should be at the level of the pyloric bulb, past midline, if you see it anywhere else, it is abnormal.

Axial contrast enhanced CT stack of the abdomen and pelvis demonstrates malrotation of the bowel with nearly the entire colon within the left hemiabdomen and small bowel in the right hemiabdomen without evidence of obstruction. This is also called NONROTATION, and rightly so!

Coronal contrast enhanced CT stack of the abdomen and pelvis demonstrates malrotation of the bowel without evidence of obstruction.

Coronal contrast enhanced CT MIPS in a different patient demonstrate reversal of the normal SMA/SMV relationship. The SMA courses to the right of the SMV. Note how the large bowel appears to be contained on the left-side, with the right hemiabdomen containing only small bowel. Try playing the video several times to understand the abnormal anatomy better.

What do I need to do?

Get ready to get your fluoro game on. Since an upper GI is still the study of choice for the surgeons, they will likely need you to do this as soon as they are consulted. This is a surgical emergency so any suspected patient would quickly need to be screened by Radiology before they are taken up to the OR emergently to save the bowel.

Selected References

1. Dunn EA, Olsen ØE, Huisman TAGM. The Pediatric Gastrointestinal Tract: What Every Radiologist Needs to Know. In: Hodler J, Kubik-Huch RA, von Schulthess GK, eds. Diseases of the Abdomen and Pelvis 2018-2021: Diagnostic Imaging – IDKD Book. Cham (CH): Springer; March 21, 2018.157-166.

2. S., L. B., Amar, G., & Ellen, P. (2017). Imaging of Pediatric Gastrointestinal Emergencies. Journal of the American Osteopathic College of Radiology, 6(1), 5–14. https://www.jaocr.org/articles/imaging-of-pediatric-gastrointestinal-emergencies

13. Bomer, J., Stafrace, S., Smithuis, R. and Holscher, H., 2020. The Radiology Assistant : Acute Abdomen In Neonates. [online] Radiologyassistant.nl. Available at: <https://radiologyassistant.nl/pediatrics/acute-abdomen/acute-abdomen-in-neonates> [Accessed 2 August 2020].

14. Lampl, B., Levin, T. L., Berdon, W. E., & Cowles, R. A. (2009). Malrotation and midgut volvulus: A historical review and current controversies in diagnosis and management. In Pediatric Radiology (Vol. 39, Issue 4, pp.359–366). Pediatr Radiol. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00247-009-1168-y

15. Bhatia, S., Jain, S., Singh, C. B., Bains, L., Kaushik, R., & Gowda, N. S. (2018). Malrotation of the Gut in Adults: An Often Forgotten Entity. Cureus, 10(3). https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.2313

16. Rokade, M. L., Yamgar, S., & Tawri, D. (2011). Ultrasound “ Whirlpool Sign” for Midgut Volvulus. Journal of Medical Ultrasound, 19(1), 24–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmu.2011.01.001

19. Wong, K., Van Tassel, D., Lee, J., Buchmann, R., Riemann, M., Egan, C., & Youssfi, M. (2020). Making the diagnosis of midgut volvulus: Limited abdominal ultrasound has changed our clinical practice. Journal of Pediatric Surgery. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2020.04.012

20. Bass, K., Rothenberg, S., & Chang, J. (1998). Laparoscopic Ladd’s procedure in infants with malrotation. Journal of Pediatric Surgery,33(2), 279-281. doi:10.1016/s0022-3468(98)90447-x