Appendicitis

What is it?

Appendicitis is the most common surgical emergency in children presenting with acute onset abdominal pain, representing up to 80% of pediatric surgical emergencies (2, 4) and is therefore the most important condition to be familiar with. While age does not serve as an exclusion criterion, appendicitis most frequently occurs in children aged 10-19 years (3).

How does it happen?

The central tenet in the pathophysiology of acute appendicitis is luminal obstruction which may be secondary to an appendicolith, fecalith or lymphoid tissue. Since the appendix is a blind ending tubular structure, obstruction of its lumen is essentially a form of closed loop obstruction which initially leads to progressive appendiceal distension as the organ continues to secrete mucosal fluid, followed by significant inflammation, bacterial overgrowth, wall necrosis and eventually perforation with or without abscess formation.

What do I need to know?

Imaging of acute appendicitis usually begins with ultrasonography because of its low cost, portability, lack of ionizing radiation and ability to achieve manual compression of the appendix to very specifically demonstrate the distention. Ultrasound has been shown to have an overall sensitivity of 72.5% and specificity 97% in diagnosing appendicitis in one large multicenter trial (5) closely approaching the diagnostic accuracy of CT.

What do I need to look for?

Sonographic Findings

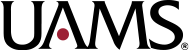

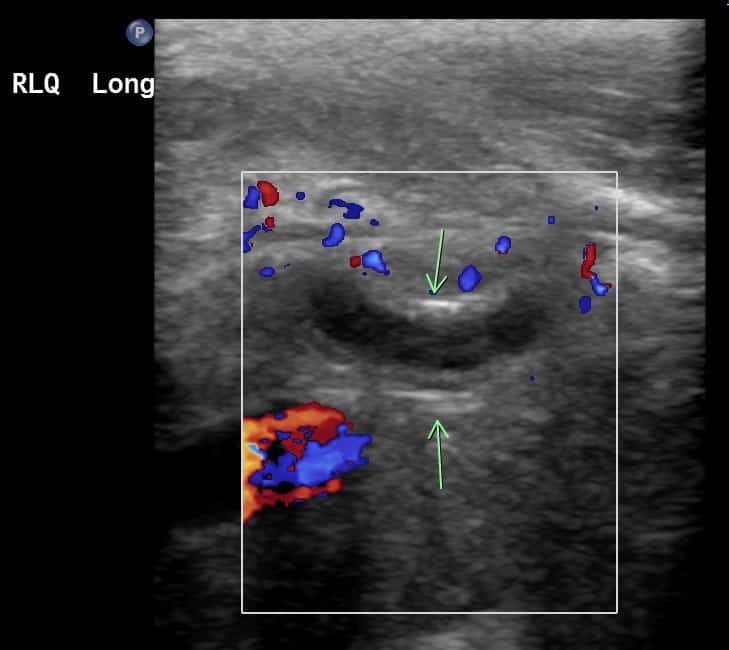

Direct Signs

- Non compressible, blind ending tubular structure in the right lower quadrant

- Dilation >6 mm

- Appendiceal wall hyperemia

- Appendiceal wall discontinuity

Supportive Signs

- Presence of an appendicolith

- Mesenteric thickening and hyperechogenicity

- Adjacent periappendiceal echogenicity

- Pericecal/periappendiceal free fluid

- Enlarged mesenteric lymph nodes

- Localized tenderness on compression (Mcburney’s Point)

Complications

Abscess formation

Look for a complex hypo echoic fluid collection. You may see an avascular center with peripheral hyperemia.

If you can’t see the appendix on ultrasound, we usually get a cross sectional study (CT/MR) to confirm appendicitis and/or look for an alternative diagnosis. CT with IV and oral contrast is usually preferred over MR despite the risk of ionizing radiation due to significantly faster scan times, allowing for decreased use of sedation, however with recent advances in MRI, it is being utilized more in some centers than in the past especially with the development of rapid MRI techniques that use no contrast agents or sedation (3).

CT Findings

Direct Signs

- Wall thickening and hyperenhancement

- Wall discontinuity

- Adjacent periappendiceal inflammation

Supportive Signs

- Calcified appendicolith

- Base of cecum inflammation

- Enlarged mesenteric lymph nodes

Axial contrast enhanced CT stack demonstrates an enlarged and inflamed appendix with large volume surrounding complex fluid concerning for perforation.

Complications

- Abscess formation

- Look for localized fluid collections with or without rim enhancement

- May be phlegmonous changes (developing abscess) at the time of scan

- Measure abscess cavity

- Generally, if the abscess >3 x 3 x 3 cm, IR guided percutaneous drainage may be considered before eventual appendectomy (6)

- Perforation

- Focal defect/discontinuity in the appendix wall

- Extraluminal gas

- Poor visualization of the appendix with diffuse ileus and peritoneal enhancement

Coronal contrast-enhanced CT stack demonstrates an enlarged and distended appendix measuring up to 0.9 cm with mural thickening and distal appendicolith (arrow). There is significant surrounding fluid and stranding in the right lower quadrant. Findings consistent with perforated appendicitis.

Contrast this with axial contrast-enhanced CT stack demonstrating uncomplicated appendicitis. Note distended fluid-filled appendix with circumferential mural thickening and wall edema as well as reactive inflammatory stranding.

What do I need to do?

Call the team if you see an appendix already ruptured, an abscess (specify if drainable, size, location, image number so they can see it and plan access), reactive fluid surrounding an inflamed appendix (which can be seen with microperforation) or other complications like bowel obstruction or venous thrombosis.

Selected References

2. S., L. B., Amar, G., & Ellen, P. (2017). Imaging of Pediatric Gastrointestinal Emergencies. Journal of the American Osteopathic College of Radiology, 6(1), 5–14. https://www.jaocr.org/articles/imaging-of-pediatric-gastrointestinal-emergencies

3. Gadiparthi, R., & Waseem, M. (2020). Pediatric Appendicitis. In StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28722894

4. Leung, A. K. C., & Sigalet, D. L. (2003). Acute Abdominal Pain in Children – American Family Physician. In American Family Physician (Vol. 67, Issue 11). www.aafp.org/afpAMERICANFAMILYPHYSICIAN2321

5. Mittal, M. K., Dayan, P. S., Macias, C. G., Bachur, R. G., Bennett, J., Dudley, N. C., Bajaj, L., Sinclair, K., Stevenson, M. D., & Kharbanda, A. B. (2013). Performance of ultrasound in the diagnosis of appendicitis in children in a multicenter cohort. Academic Emergency Medicine, 20(7), 697–702. https://doi.org/10.1111/acem.12161

6. Leite, N. P., Pereira, J. M., Cunha, R., Pinto, P., & Sirlin, C. (2005). CT evaluation of appendicitis and its complications: Imaging techniques and key diagnostic findings. In American Journal of Roentgenology (Vol. 185, Issue 2, pp. 406–417). American Roentgen Ray Society. https://doi.org/10.2214/ajr.185.2.01850406