Non Accidental Head Trauma

What is it?

Approximately 1 in 3 children subjected to non-accidental trauma experience abusive head trauma, which unfortunately remains a major cause of morbidity and mortality in the abused pediatric population with mortality rates of more than 15% (6, 7).

How does it happen?

Strangulation results in the classic hypoxic-ischemic injury pattern, which is detailed below. Also note, bimanual assault usually produces bilateral injuries, which may be the first sign of strangling (7).

What do I need to know?

There are two main categories of neurological assault, shaking injuries (leading to subdural and retinal hemorrhages), and direct impact trauma causing coup/contrecoup injuries and skull fractures. Commonly, impact type injuries can cause depressed skull fractures, cortical contusions and extradural hemorrhage. Most common presentations of non-accidental trauma include – in order – interhemispheric subdural hematomas, cerebral edema and subarachnoid hemorrhage followed by infarct/ischemia (5).

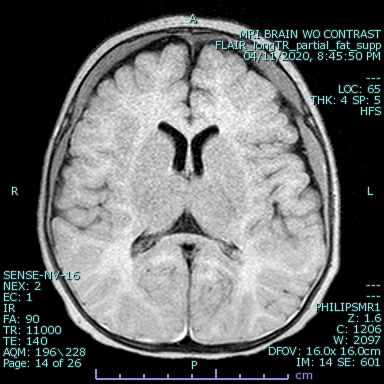

The classic ‘white cerebellum sign’ documented in pediatric victims of assault with irreversible hypoxic brain damage is uncommonly seen and denotes a poor prognosis (8). It is believed that the brainstem, cerebellum and thalamus may be selectively spared in early ischemia due to preservation of posterior circulation by autoregulation (7).

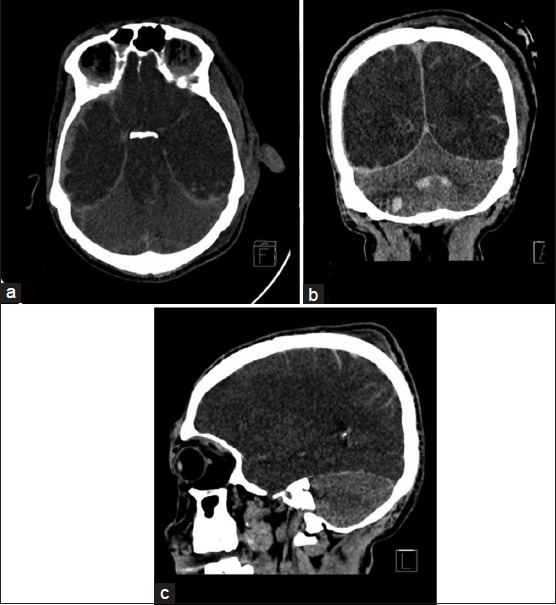

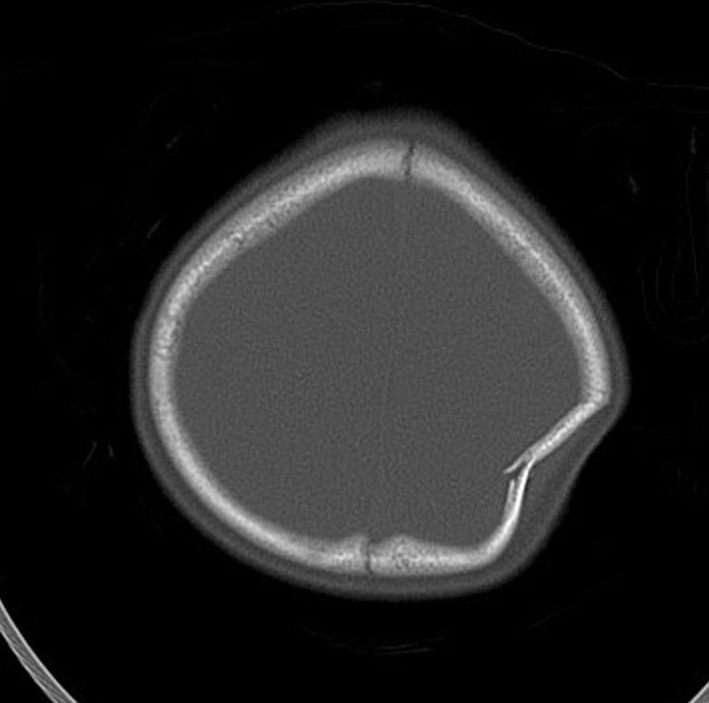

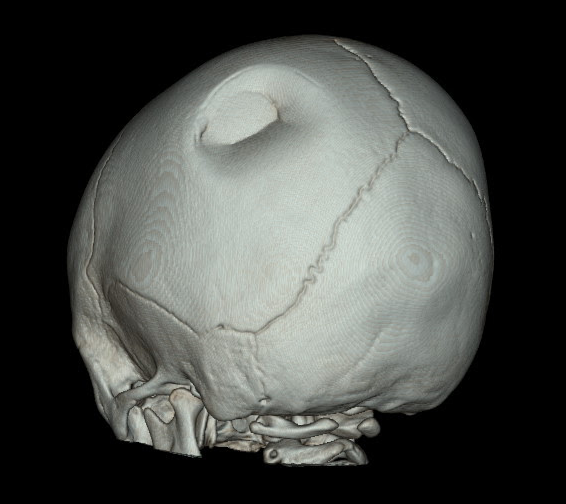

Depressed skull fractures are frequently associated with underlying intracranial injury. In our institution, all pediatric low dose trauma CT scans of the head include axial, sagittal and coronal reformations as well as 3D reconstructions to distinguish true fractures from normal sutures.

Ping pong fractures are specific skull fractures seen in neonates with soft and resilient calvaria which are able to indent without sustaining an actual break in the bone. This is similar to the mechanism for greenstick fractures in the long bones. These fractures are rarely associated with intracranial injury (9).

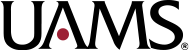

Although CT is usually sufficient to diagnose non accidental head injuries in children, MRI can be obtained for additional signs of injury and confirming evidence of repeated injuries (2).

What do I need to do?

Call the emergency department to discuss the findings with the ER physician and document it on the preliminary report.

Selected References

2. Huang, B. Y., & Castillo, M. (2008). Hypoxic-Ischemic Brain Injury: Imaging Findings from Birth to Adulthood. Radiographics, 28, 417–419. https://doi.org/10.1148/rg.282075066

5. Ashwal, S., Wycliffe, N. D., & Holshouser, B. A. (2011). Advanced neuroimaging in children with nonaccidental trauma. Developmental Neuroscience, 32(5–6), 343–360. https://doi.org/10.1159/000316801

6. Rolfes, M., Julie, G., Brucker, J., & Kalina, P. (2019). Article – Neuroimaging of pediatric abusive head trauma. Applied Radiology, 3, 30–38. https://www.appliedradiology.com/communities/Pediatric-Imaging/neuroimaging-of-pediatric-abusive-head-trauma

7. Hsieh, K. L.-C., Zimmerman, R. A., Kao, H. W., & Chen, C.-Y. (2015). Revisiting Neuroimaging of Abusive Head Trauma in Infants and Young Children. American Journal of Roentgenology, 204(5), 944–952. https://doi.org/10.2214/AJR.14.13228

8. An, M., Abam R, & Mp, O. (2019). White Cerebellum Sign-An Ominous Radiological Imaging Finding: A Case Report and Review of the Literature. Biomedical Journal of Scientific and Technical Research, 15(1), 11159–11161. https://doi.org/10.26717/BJSTR.2019.15.002659

9. Zia, Z., Morris, A.-M., & Paw, R. (2007). Ping-pong fracture. Emergency Medicine Journal : EMJ, 24(10), 731. https://doi.org/10.1136/emj.2006.043570