By Marty Trieschmann

UAMS Palliative Care Lecture Sparks Discussion on End-of-Life Communication

Sarah Harrington, M.D., medical director of the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences (UAMS) Palliative Care Program, is on a mission to help other physicians understand the delicate nature of communicating with patients facing serious illnesses.

“There are a lot of difficult conversations we have to have at profound moments,” said Harrington, director of the UAMS Division of Palliative Medicine since 2008. “How we use language in these moments is so important, but it’s not something all physicians are trained to do.”

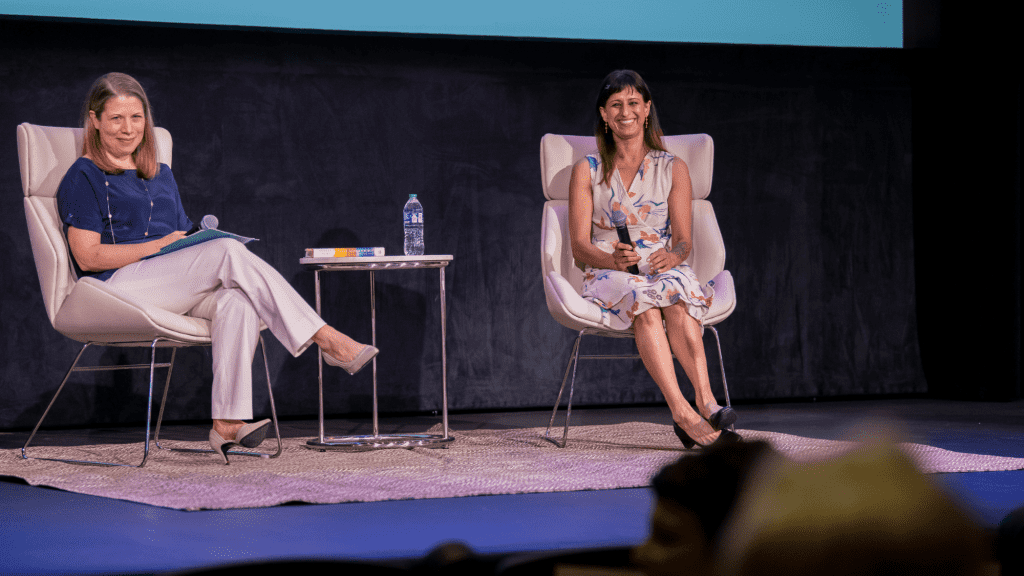

The role of language was one of the main topics of discussion at a fall guest lecture presented by the division. The event, titled “That Good Night: On Dignity, Suffering & the Role of Medicine in Life’s Eleventh Hour,” was made possible by a grant from the Dorothy Snider Foundation. This is the second year of the series.

In September, Sunita Puri, M.D., author of “That Good Night,” spoke to a group of 100 guests at Ron Robinson Theater in Little Rock about her experiences with patients facing serious illness. Puri is the director of the Hospice and Palliative Medicine Fellowship at the University of Massachusetts Memorial Medical Center and the Chan School of Medicine, where she is an associate professor of clinical medicine. The following day, Puri spoke to UAMS faculty and students on campus at the first Palliative Medicine Grand Rounds.

Puri’s book struck a chord with the UAMS palliative care faculty.

“She talks about holding space for patients and families to have hope,” said Harrington.

“It’s a difficult thing for physicians to navigate, but we can have both.

“Don’t tell a patient, ‘There’s nothing more we can do.’ “That’s terrible. There is always something we can do. We can always provide specialized patient-centered care, especially at the end of life.”

The Palliative Care Team treats patients within the Winthrop P. Rockefeller Cancer Institute and the UAMS Medical Center. Most of their patients have cancer, end-stage heart failure, dementia or other serious illnesses

“We always have to balance hope and reality,” said Harrington. “We have to explain to patients how a disease course is likely to go while being open that there is always a certain amount of uncertainty.”

Harrington says the lecture sparked good conversations about dealing with uncertainty in prognosis and navigating difficult conversations.

“Many patients have years to live,” she said. “Our job is to help manage their symptoms and give them the best quality of life. There’s a lot of good we can do at this stage of an illness.”